In Part 1 I used my experiences with tourettes and OCD to look at Dracula.

In Part 2 I looked at Alucard’s history of abuse and how it has marked him.

Now in the final part of this series, I’m going to look at Alucard’s childhood home, and the location of nearly every entry in the Castlevania series. What can we glean about Alucard from exploring Dracula’s castle and interacting with the creatures therein?

At the second meeting between Alucard and Maria, she remarks on how different the castle is from what she saw as a child, a meta-commentary on how a series with 14 previous installments, all taking place at least partially in the same castle, can have different stage layouts. Alucard then reveals a clever bit of justification: the castle itself is a living being of pure chaos. It changes from game to game because the castle is alive and responding to the moods and whims of its master. Maria accepts this quickly (but then, she’s presumably dealt with stranger information before) and remarks that this means they can’t trust their memories. For her this means the memories of the previous game, Rondo of Blood but for Alucard it means something more.

What are Alucard’s memories of growing up in Dracula’s castle? What was it like living in a castle that shifts and rearranges itself. We don’t know how often the castle takes on a completely new layout. Year to year? Decade to decade? Could each day offer a surprising new room? Is there even a pattern at all? How much of this castle does Alucard even recognize? For that matter, how many of its denizens does Alucard recognize?

When Alucard starts the game, he is decked out in the most powerful equipment. He carries a sword, armor and shield all bearing his name, a special cloak for vampires, and a horned helmet belonging to Icelandic hero Egil Skallagrimsson. He easily cuts a swathe of destruction through the introductory section of the castle, knocking down giant wolves in a single blow and shrugging off zombie claws, up until he encounters Death itself, who strips him of his inheritance and leaves him a puny weakling.

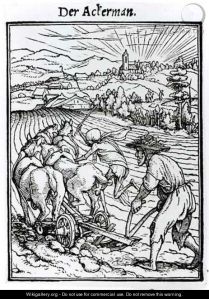

Death is a reoccurring character in the Castlevania series, usually Dracula’s right-hand man. He always first appears as a stereotypical grim reaper figure. Death’s Japanese name, Shinigami, refers to a collection of death spirits/gods in Japanese mythology, but his appearance in this game is clearly that of the singular Western representative of death. There are many, MANY personifications of death throughout European folklore and history, but the skeletal grim reaper figure we know today has its roots in the Jewish tradition of the Malach HaMavet, or the Angel of Life and Death. This is the figure that reaps the firstborn of Egypt. It is worth noting that this Angel of Death is not an evil creature but rather a force of nature under God’s control. Non-biblical Deaths from the area were psychopomps that guided people to the underworld, and were often positive figures that eased pain and helped guide people to where they needed to be. The event that changed how the average European viewed death would take place in the late 14th century. The black plague was a pandemic unlike any other than Europe had experienced. 25 million people died in the initial outbreak, and millions more died in the centuries that followed with an estimated final death count as high as 200 million. Death was no longer an abstract, but reasonable condition. It was now something (or someone) that came indiscriminately and constantly, taking everyone you knew and loved in the most painful method possible and clogging roads and cities with dead bodies. As a result of this, the transformation of Death from an angel to a skeletal figure took place around the 15th century. No longer the servant of God from the bible or the helpful psychopomp from pagan lore, Death was now mowing down people like grain and not giving a shit about anyone or anything. Death’s weapon was originally a crossbow that it would shoot at individuals, but this changed to a scythe to better represent the huge swathe of indiscriminate destruction. The Polish incarnation of the Grim Reaper, Smierc, is a female skeleton, and many pre-plague personifications of death from Europe are women, but in most other incarnations the medieval Grim Reaper is male.

Yet even in this time, there were depictions of Death that carried different connotations. A post-plague play by Johannes von Tepi, Death and the Ploughman, features a dialogue between a farmer and Death over the purpose and meaning of life and morality. Death is not evil in this play, and resents the ploughman reprimanding him for the death of his lover. Death argues that his existence is the great equalizer, coming to even the most powerful, and that his existence is what gives life meaning, while the ploughman is quick to point out that he found plenty of meaning with his beloved before her death, and that the sorrow of her passing is not the origin of their joy but the end, tainting his happy memories with bitterness and sorrow. He also points out that, despite his claims as being a great equalizer, Death is not guaranteed to come to the wicked before it comes to the virtuous, and so Death’s attempts at claiming neutrality are actually anything but. Rather by being “equal” Death renders good and evil moot, as morality is then not a guarantee of a good life. Death counters this by noting that anyone expecting a reward for being moral is not moral at all. In the end, their debate reaches an impasse, and God watches both from on high and notes that neither is able to see beyond themselves to the true reality of the world. This play is considered to be one of the literary foundations of the later humanism movement. In the tarot deck, Death is the thirteenth Major Arcana. While still depicted as a skeletal figure, it represents transition and transformation. Death is followed by regeneration, and the death of a negative part of the self can allow the positive parts to grow. Death is merely change, and change can be positive or negative.

Death is without a doubt a negative figure in Castlevania both in the abstract sense and in terms of the actual character. Death of the player means failure, and Death the character is an enemy that can only be engaged with through conflict. However, there is some thematic connection to Death’s positive features as well. Death’s first encounter with Alucard is certainly a transition, stripping away the physical connection Alucard has to his past in the form of his equipment and forcing him to relearn and rediscover his power. By stripping away the powerful equipment, Death forces the player to define Alucard themselves and forces Alucard to understand himself. In terms of the larger plot, their encounter gives us a few hints into Alucard’s past as well. He tells Alucard that he won’t ask him to return to the side of darkness, indicating that he is familiar enough with Alucard to know he has made his decision. Other than that, he speaks to Alucard in the manner of an authority figure reprimanding a disobedient child. Alucard’s previous history with Death is never stated, but we can infer a lot about their relationship based on the few snippits of dialogue. Presumably, Alucard was tolerated as Dracula’s offspring, but little else.

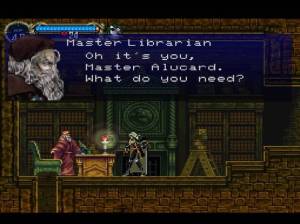

There are only two other residents of the castle Alucard has direct communication with, the Succubus and the Librarian. The Succubus is not a figure from Alucard’s past, but he clearly recognizes and remembers the Librarian. Alucard speaks to the old man with more affection than he does anyone else (albeit still not much). While the Librarian will not move against Dracula directly, he has no problem selling Alucard weapons and magic, and Alucard knows him well enough to suggest this arrangement in the first place. Perhaps young Alucard spent a lot of time in the Long Library. Growing up in a haunted castle without any peers, it is easy to imagine Alucard as a shy, bookish child. While Dracula was off ranting about humanity or raising an undead army, perhaps Alucard slipped away to the library to read about the outside world. Through reading, perhaps Alucard was able to first learn and connect with the human part of himself that Dracula neglected.

Tellingly, this is the only part of the castle with any implied relevance to Alucard’s past. Alucard does not communicate with any other denizens nor does he remark on any other section. However, there is one way for Alucard to interact with the castle. By pressing the up button in front of certain chairs, Alucard will sit down and relax in them. There is no gameplay purpose to this act and it does not affect Alucard’s stats or abilities in any way. So why include this feature? By letting Alucard stop and interact with the furniture, the game creates a little moment for the player to stop and reflect, if they so choose. What is Alucard thinking when he sits in a chair along the castle’s Outer Walls as opposed to sitting in the Marble Gallery? What memories do these locations bring to mind, if any? Alucard is revisiting his childhood home, one that has changed a great deal since he left. This is an experience nearly every player can relate to, especially those of us returning to the game as adults. In some cases, we may even be playing the game while we sit in chairs (new and old) within our own childhood homes. Through this simple, “useless” mechanic, the player can see and connect to Alucard’s story behind the battles and monsters. The story of an estranged child returning home.

Dracula’s castle has many wings dedicated to specific uses. He has his Alchemy Lab, his Marble Gallery, his Colosseum and even a Chapel (and odd choice for a dedicated servant of darkness and chaos). What it doesn’t have is Alucard’s old bedroom. If the castle is changing depending on the needs of the inhabitants, it may simply have swallowed them up once Alucard left. It could always create a new bedroom if Alucard ever returned to the fold. However, it is implied that the castle changed based on the whims of its master rather than its own desires. If this is the case, than it represents a deliberate cutting of ties by Dracula. Alucard chose to stand with Dracula’s hated enemies, and while he did so in response to abuse and neglect at Dracula’s own hands, Dracula is not by nature a creature of self reflection. To Dracula, Alucard is a traitor first and foremost. The destruction of Alucard’s old quarters speaks volumes on how Dracula thinks of his son. He does not expect, nor apparently desire, Alucard’s return.

There is another possibility, that Alucard’s room IS still there, just not in a form we recognize. After all, Alucard has been gone for hundreds of years, and while Dracula was dead for large periods of that time, its also possible that he kept Alucard’s room as it was for awhile. Once he knew Alucard was not coming back, he did what all parents do once their children establish independence: he converted the room. Maybe Dracula’s apparent alchemy hobby came about once he was able to turn Alucard’s wing into a lab, or maybe he converted it to showcase his collection of marble statues and grandfather clocks. Or maybe Dracula rented out the space to a new lodger.

Of all Dracula’s castle, the most inexplicable wing is Olrox’s quarters. The entire wing is nearly bare, with none of Dracula’s usual art or style adorning its walls. Further in, there is only a collection of jail cells filled with lonely ghouls. There is a courtyard where the player can see an empty village in the background, but that is about it. Even the enemies here are pretty bare bones (pun not intended) with only a few skeletons, zombies and dead warriors. The only room with any decoration is Olrox’s banquet hall, where the player can stop and (you guessed it) sit at the other end of the table before engaging Olrox in battle.

Olrox is a vampire and clearly meant to invoke Count Orlock of the classic 1922 film Nosferatu. The film was made before Bram Stoker’s Dracula entered the public domain, so the studio attempted to get around the copyright issue by creating their own vampire. Their tactic failed, and Stoker’s heirs successfully sued, resulting in almost every print of the movie being destroyed. Olrox resembles Orlock, a tall gaunt figure with long fingers and a bald head. The fact that his battle takes place in a banquet room calls back to the famous scene from the original movie where Thomas Hutter (who is totally not Jonathan Harker!) first suspects Count Orlock’s supernatural origin (Thomas cuts his finger slicing bread and Orlock immediately grabs Thomas’ finger and jams it into his mouth. This leads Thomas to suspect that maybe the nobleman frantically drinking blood from his finger may not be what he seems). Just as movie Orlock was a movie Dracula-rip off, Orlox fights like a lesser version of Castlevania’s Dracula, complete with his own final, true form.

As a child, I had assumed Olrox must be a powerful ally or friend of Dracula to get his own wing. Now I wonder if he was just a squatter or lodger. This bare, empty wing of the castle seems to be forgotten by Dracula. If this is where Dracula leaves things he’d rather forget, it would make sense that he’d make it the quarters of his neglected, half-human son. Alucard reminds Dracula of his failures and his enemies, so he stuffs him out of sight and out of mind. This is all speculation of course, as this part of the castle has a distinct lack of interesting items as well, giving no hints as to Alucard’s connection, if any, to the area.

The only other creature Alucard speaks with is the Succubus impersonating his mother. From this encounter we learn what happened the day of his mother’s execution, and how his mother asked both him and Dracula to forgive humanity. We also see Alucard get actually upset for the first time. The veil of aloofness drops, and Alucard expresses shock and emotion at seeing his mother once again, followed by disgust and anger at the deception. Surprisingly, we also learn that the Succubus wasn’t even aware of who Alucard was, only suspecting he is Dracula’s son after she is killed. The Succubus wasn’t part of any plan to win Alucard back to Dracula’s side and wasn’t acting on Dracula’s orders, but was rather just a demon messing with someone who wandered into her lair. Again we see evidence that Dracula does not give much of a shit about bringing his son back to his side.

As for the hundreds of other demons, spirits and undead in the castle, if Alucard recognizes them he doesn’t give any indication. It stands to reason that growing up in the castle as part of Dracula’s dark army, he would have known a few monsters. We can only speculate what this would have been like. Did Alucard play games with fleamen? Smoke cigarettes behind the Outer Wall with Slogra and Gaibon? Share a first kiss with the top or bottom half of an amphisbaena? Is he slaughtering old friends? But then, even if he did have monster friends growing up, who is to say they’d still be alive (or undead) today? Getting the good ending results in meeting every enemy just as it results in seeing every part of the castle and mastering every one of Alucard’s abilities. But just as before, what’s important to know is the fact that Alucard is relearning the castle, not what he specifically thinks and feels about it. The specifics of what he feels and what his encounters mean is unknowable, expressed only in player theory and how they choose to control their version of Alucard.

hmm…that last picture is a bit unsettling you know… ;(

Pingback: This Week We Read: 02/11/14 « Normally Rascal

Pingback: Abnormal Mapping 37: A Miserable Pile of Dicks | Abnormal Mapping